by Brendan Sutcliffe~

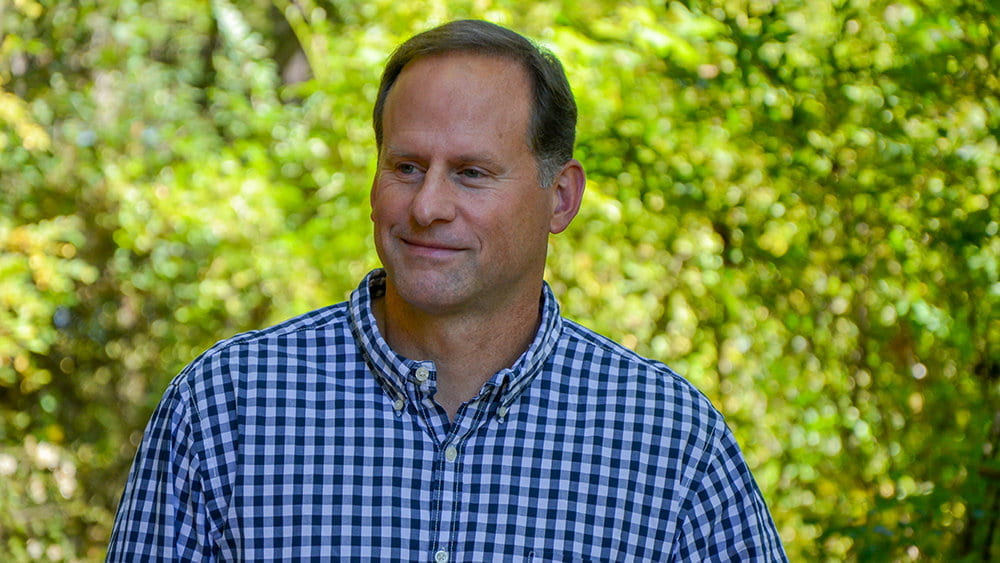

It was a beautiful fall evening in 2018 when I was taking the bus at Penn State Altoona to my creative writing class, thinking: How on earth will I get through this? I am an English major, but creative writing was never my strong suit, and the three-hour-long class was on Tuesdays — my busiest day. When I got to class, my professor Todd Davis was standing in the front with an inviting grin on his face. He began class by telling us about his interesting background and life and then began to read some of his poetry. I immediately changed my thinking about the class.

Todd Davis is a Professor of English and Environmental Studies at Penn State University’s Altoona College. What I didn’t know when I enrolled in his ENGL 50 (Intro to Creative Writing) course was that he is the author of six books of poetry: Ripe (2002), Some Heaven (2007), The Least of These (2010), Household of Water, Moon, and Snow: The Thoreau Poems (2010), In the Kingdom of the Ditch (2013), and his newest book Native Species (2019), as well as a co-editor with Erin Murphy of the anthology Making Poems (2010).

The winner of the Gwendolyn Brooks Poetry Prize (awarded by the Society for the Study of Midwestern Literature), Davis has published poems in numerous national and international journals and magazines, including Poetry Daily, Verse Daily, The North American Review, The Iowa Review, The Gettysburg Review, Indiana Review, The Christian Science Monitor, Orion, Shenandoah, River Styx, Sou’wester, 5 AM, Quarterly West, Green Mountains Review, Poetry East, West Branch, Epoch, The Louisville Review, and Image.

As a recent student who has witnessed first-hand the way his poetry can make you feel, I was pleased to talk with my former professor Dr. Davis again and to be able to share his insights with you. Below are edited highlights of the interview.

BS: What was your main attraction to poetry and what inspired you to begin a career in it?

TD: I loved the music in poetry, the sound play and rhythm, but the true attraction for me was the power of the image, the way particular images could evoke or represent emotion without simply stating it. I think I liked that poetry could make a gesture toward the difficulty of some human situation without becoming reductive. I was drawn to such poetic slogans as William Carlos Williams’ “No ideas but in things!” and to the Jungian notion of shared patterns and images that have a deep evolutionary history.

BS: How do you think your childhood and experiences have affected your writing?

TD: I grew up in a factory town on the border of Michigan and Indiana. I’ve always lived in Rust Belt regions. Because of this, I write about the working class and with the working class in mind as my audience. My grandparents were farmers and my father was a veterinarian. Because of this, I’ve spent much of my life in relationship with other-than-human animals and they populate many of my poems.

BS: Being a creative writing professor at Penn State, have you noticed a lack of interest in poetry with students throughout the years? And if so how can educators combat that issue?

TD: In general, poetry is not one of the arts that many Americans read regularly. In this way, students at Penn State are similar to the broader public. But there are people who love poetry, and there are more people who turn to poems during emotional upheaval, during times of grief, or sometimes in celebration and joy.

As for how to combat the issue, or how to invite more people into poetry, I think it’s about finding poems that connect with a person’s experiences and introducing them to poems that are more welcoming, that allow meaning-making upon an initial read. If you fall in love with poetry, you’ll move on to more difficult poems. I think too often we introduce students to poetry with poems that are oblique, that thwart meaning-making.

BS: Why do you think it’s important for young people to be exposed to poetry?

TD: Like all of the arts, I think it’s important for young people to interact with poems because it opens the possibility for them to gain insight into the human dilemmas we face, to imagine themselves across boundaries, to hopefully develop compassion and empathy, to explore and celebrate language.

BS: What in your opinion do you believe makes a good poet and what tips would you give to Penn State students on how to be a successful one?

TD: I think for most of us, to practice an art successfully, you must have a degree of understanding of its history, of its aesthetics, of the techniques and skills, of the possible forms and how those forms can be circumvented or built upon. To have that understanding, a writer must read and read and read. Read contemporary poets, read poets from across the history of the genre. Then apprentice yourself to a living poet, or one of the poets you’ve been reading. Be willing to listen to critique from others, which means being humble, but also be willing to have confidence in your vision as a writer. Ultimately, there is no blueprint for writing a poem. We look for an authentic voice in a poem. We look for details that connect to our senses. We look for fresh language, for freedom and play.

BS: Do you believe the internet and social media have benefited the way poetry is discovered and consumed, why or why not?

TD: Like so much of the Internet (and the accompanying social media), there are definite positives. The positives include access to more poems.

I start my day each morning by reading the poem on Poetry Daily, Verse Daily, and Poem-a-Day from the Academy of American Poets. There is such variety in contemporary poetry, and if a writer wants to find a poet to connect with, the Internet certainly provides that.

Having said that, the Internet and our obsession with screen time is not a big help when it comes to writing poems. Making poems requires the ability to focus for long periods of time, to meditate on language, to cross-examine what we’ve written, to let the writing sit for a time and come back to it. None of these things are aided by the short-attention-span the Internet encourages or grooms.

BS: How important is accessibility of meaning? Should one have to work hard to “solve” the poem?

TD: I try to write a poem that is accessible upon a first reading. However, I hope that I have layered meaning in my poems and that subsequent readings open up new meanings or deeper levels of meaning.

BS: Has your idea of what poetry is changed since you began writing poems?

TD: I hope I’m getting better as a poet. There’s so much to learn about poems. More than can be learned in a lifetime. So, yes, I continue to expand my understanding of poetry. I continue to be surprised by poems. I continue to be challenged by poems. And I continue to try to expand what I can do in a poem.

BS: Do you have a writing group or community of writers you share your work with? Who are they?

TD: Yes, I can’t imagine writing without a community of writers to read my work honestly and offer criticism and encouragement. For my most recent book, Native Species, the following writers read the manuscript and helped make it better: K.A. Hays, David Shumate, Lee Peterson, Steve Sherrill, and Noah Davis.

BS: One of the poems I read from your new book Native Species that I really enjoyed was “Almanac of Faithful Negotiations.” What about this poem do you find special or inspired you to write it? Where did the idea for this poem stem from?

TD: I’m interested in how energy is constantly transformed, how the movement from birth to death is a pilgrimage of transferal. Those are the ideas behind this poem. But, at least for me, poems are comprised of the “real” things of the world. That’s why this poem is populated with animals, with all kinds of other species, moving toward mortality but with hints of the spiritual world that is intertwined with the physical world.

Meet the poet! Todd Davis will give a reading as part of the Mary E. Rolling Reading Series on the University Park Campus, on November 14, 7:30 pm, in Foster Auditorium, Paterno Library.