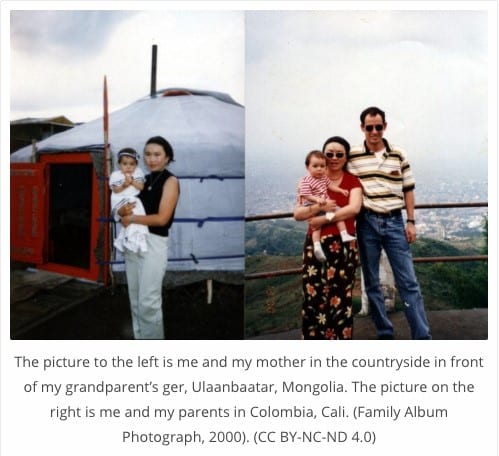

I am Mongolian and Colombian. As a child, I never quite understood why it was so rare to be such a mix. Since kindergarten, I’ve been traveling around the world, spending almost each school year in another country due to my father’s work. I desired a place to call home in which I could buy things without worrying about moving. As I traveled, a part of me was reflected in each country. I was not meant to be part of a single ethnicity or country; I am a global citizen. Earth became my home.

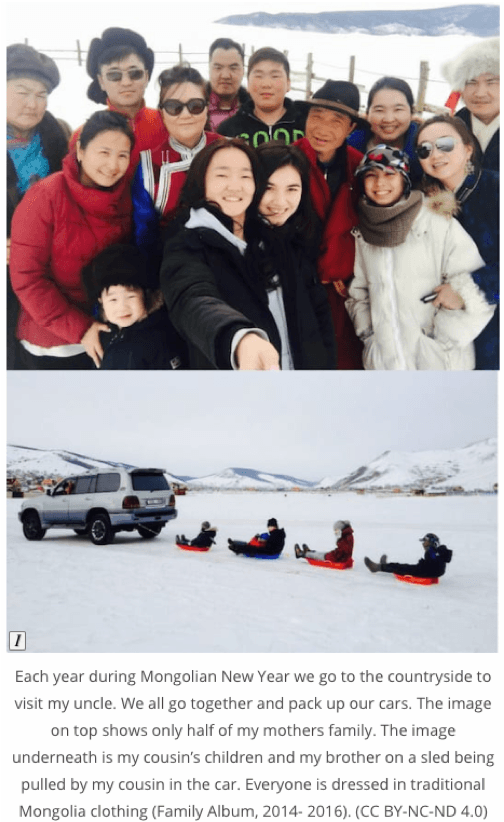

My parents met in Mongolia through work. They both came from a big family of ten. I also grew up with alarge and loud family, celebrating Christmas and Tsagaan Sar. My parents merged all of their traditions and celebrated every single one with us, making life more fun than a child would expect. This meant twice the holidays than anyone else and more gifts

As the years passed by I saw my classmates live in one country with a settled home and a place to keep all of their belongings. I started questioning why I did not have such a place. I was not the only one in this situation. Biracial people around the world suffer from racial imposter syndrome (Donnella, 2017). It is the feeling of not fitting in any race or being perceived as a race you are not. Everything I owned was all over the place, including Qatar, Colombia, and Mongolia. My classmates would designate home as the place you grow up, but I grew up all over the world. I started traveling before I turned a year old, unlike 82% of the world who never flew on a plane (Mandyck, 2017).

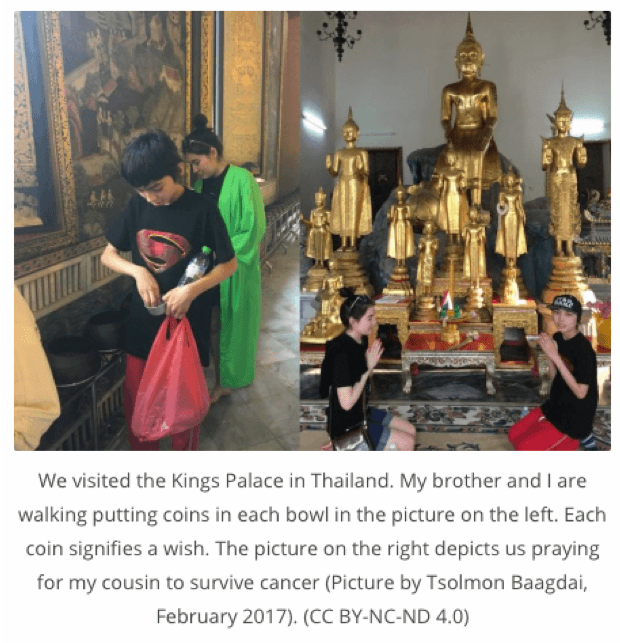

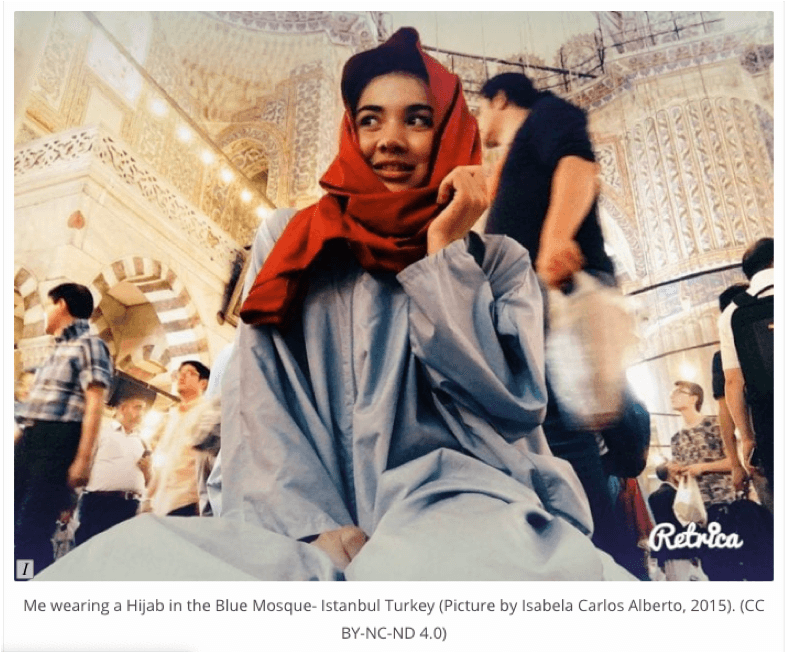

Others would say it is the culture of my family that defines where I am from. That did not apply to me either because I hold values from many cultures. All the values I collected are from all over the world. For instance, I was baptized in Colombia, but I go to temples to pray and follow the Mongolian Lunar New Year. When we lived in Qatar during Pre-K and first grade, the Islamic culture influenced my daily patterns. At school, I learned the first verse of the Quran in Arabic, and during Ramadan, I would receive gifts from my classmates’ parents. Not only did my parents implement these traditions in our lives, but I was drawn to other traditions. For instance, I was attracted to mosques and temples. They fascinated me because every drop of worry vanishes when you walk in. Everyone shuts down and watches without a single word.

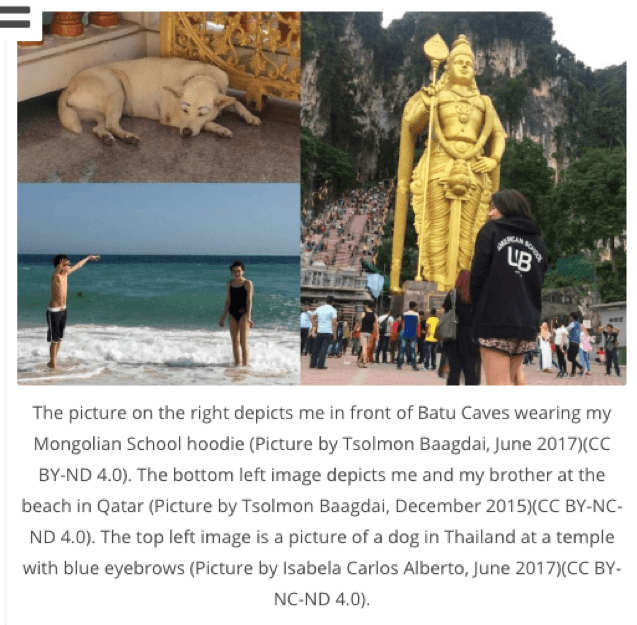

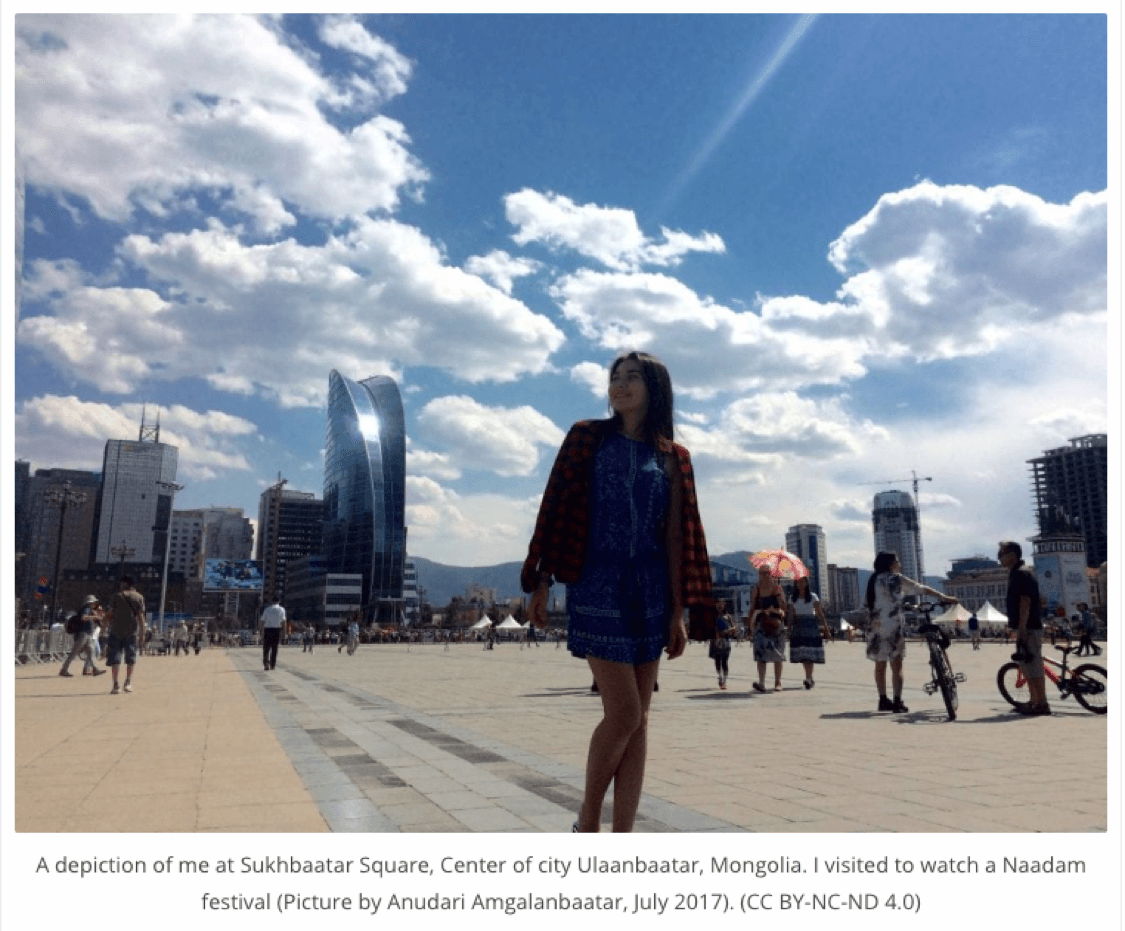

Since the start, it was impossible for me to choose one religion, culture or country, so I set forth to find the true place I belonged. It did not matter whether it was a country, religion, or culture. I traveled to Colombia, China, Korea, Turkey, Malaysia, Thailand, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Singapore, and the United States of America. I searched where I would belong the most, where the majority of Mongolian Colombians were; however, I found another part of myself. With more than 9 million multiracial people in the United States alone(Parker, Horowitz, Morin, & Lopez, 2015), and from all the places I have been, I never heard of or met a Mongolian Colombian.

Throughout my travels, I learned to respect others and their values. I ate different foods, each unique to the particular country. I realized the more you tried different cuisines the more appealing and delicious they become. In Qatar I grew fond of olives and hummus, in Colombia, I tried all the cheese and pork meat, in Mongolia I learned to make curds and tried airag (fermented horse milk), in China I tried the famous Chinese duck, and in Korea I tried every single food from restaurants to street food. In Colombia it was all about bursting salt and sugar on your tongue, Mongolia it was about the fresh juicy meat and dairy straight from the farm, and in Korea, the spicy food will sting your tongue and heat up your lips. Each culture had a core ingredient that blossomed into every single dish or course. The fresh spices and different alternative uses of a single ingredient were astonishing.

Throughout my travels, I learned to respect others and their values. I ate different foods, each unique to the particular country. I realized the more you tried different cuisines the more appealing and delicious they become. In Qatar I grew fond of olives and hummus, in Colombia, I tried all the cheese and pork meat, in Mongolia I learned to make curds and tried airag (fermented horse milk), in China I tried the famous Chinese duck, and in Korea I tried every single food from restaurants to street food. In Colombia it was all about bursting salt and sugar on your tongue, Mongolia it was about the fresh juicy meat and dairy straight from the farm, and in Korea, the spicy food will sting your tongue and heat up your lips. Each culture had a core ingredient that blossomed into every single dish or course. The fresh spices and different alternative uses of a single ingredient were astonishing.

I found similarities rather than differences everywhere I went. Designs, values, and origins of different religions all had something in common. Every religion started with someone sending ‘the message’ of becoming the right person in society.

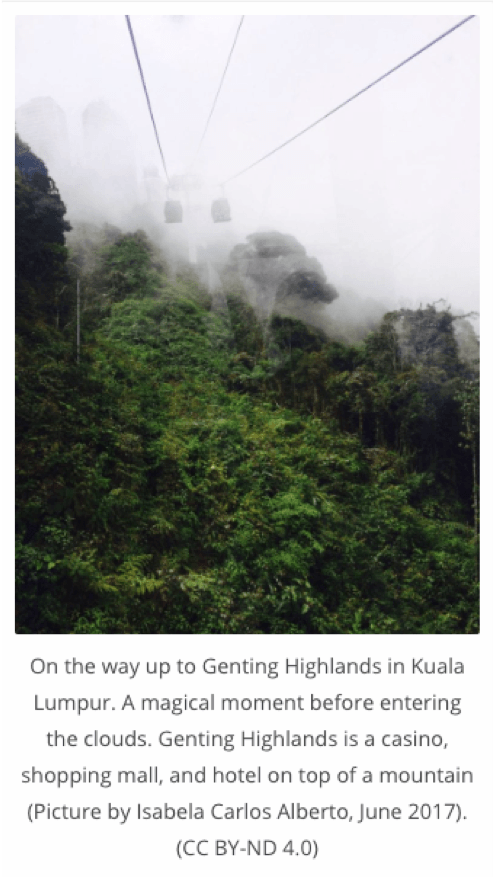

The designs and historical sites showed the globalization of each country. Every country had a historical artifact or design that came from another country. Another similarity was all the alterations of religions. In every country, they adjusted the religion slightly to fit their climate, history, and national value. For example, Buddhism in Kuala Lumpur was rather mixed with Hinduism when regarding designs, while Buddhism in Mongolia resembled the Tibet culture.

The designs and historical sites showed the globalization of each country. Every country had a historical artifact or design that came from another country. Another similarity was all the alterations of religions. In every country, they adjusted the religion slightly to fit their climate, history, and national value. For example, Buddhism in Kuala Lumpur was rather mixed with Hinduism when regarding designs, while Buddhism in Mongolia resembled the Tibet culture.

The people we came across while traveling all valued respect and were curious about other countries. People always asked about the food, culture, and technology in Mongolia. It was shocking tohear people ask if we ride horses or throw newborn infants in the snow. Nevertheless, people were kind and tried their best to help others. One time in Korea we were lost in the metro station when a man near his 50’s walked us to our train; he did not speak much English and we didn’t know a single Korean word. We communicated through hand gestures. Out of 6.9 million people who ride the metro each day in Korea, rushing to home or work, he decided to help us (Kasulisk, 2017). I learned how many kind people are out there. We may not be able to communicate but people try their best to help through hand gestures. Sometimes they even got off their course and took us to our destination. Despite all the terror in the news, the good outweighs it.

With each country, I visited I discovered a new part of me. The religion and culture were implemented in me. I adapted and was within the culture wherever I went because I found similarities, a part of myself, somewhere within. I am proud to support the idea of a global citizen because I am truly a global citizen. I can relate to all cultures. I do not have a single religious belief, nor do I have specific celebrations. I celebrate holidays from many cultures with various beliefs. All 195 countries on earth are my home (Countries, n.d.).

References

Countries in the world:195. (n.d.). Retrieved October 23, 2018, from http://www.worldometers.info/geography/how-many-countries-are-there-in-the-world/

Donnella, L. (2017, June 8). ‘Racial impostor syndrome’: Here are your stories. Retrieved October 21, 2018, from https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2018/01/17/578386796/racial-impostor-syndrome-here are-your-stories

Kasulisk, K. (2017, June 20). Transportation in Seoul shows how far behind America really is. Retrieved October 23, 2018, from https://mic.com/articles/180164/transportation-in-seoul-south-korea-shows-americans-exactly-what-were-missing#. o3J8zfEGW

Mandyck, J. (2017, December 06). Fewer than 18 percent of people have flown: What happens next? Retrieved October 22, 2018, from https://www.huffingtonpost.com/john-mandyck/fewer-than-18-of-people-h_b_12443062.html

Parker, K., Horowitz, J. M., Morin, R., & Lopez. M. H. (2015, June 11). Multiracial in America: Proud, diverse and growing in numbers. Retrieved October 23, 2018, from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/06/11/multiracial-in-america/

Isabela Carlos Alberto is a Mongolian Colombian and graduated from American School of Ulaanbaatar. Currently, she is a freshman majoring in Finance at Penn State Brandywine. Her experiences in high school include being the vice-president of National Art Honor Society, president of The Weekly Howl blog and having two gallery exhibitions in Malaysia and Mongolia. At Brandywine, she is the treasurer for Active Minds Brandywine and DMAX and the freshman chair for the Student Government Association this year.

Good luck Iza